Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo 2023: The Rodeo That Made My ’80s Baby Childhood Epic

The fourth-generation farmer and cowgirl has covered BPIR for international brands and publications to continue to storytell Black cowhand culture. | Photo By Kevin Dantes

I hooped. I hollered.

Embarrassingly loud.

To the point, spectators whipped their necks in my direction and asked, “Are you the Momma?”

Me mid cheer: “Oh, no. I’m just their biggest fan.”

I’ve never met these kids a day in my life.

But the way they turned and burned the barrels on lightning-speed steeds gets me going.

Takes now 39-year-old Cowgirl Candace back to the late 1980s and early 1990s.

When I rode as an amateur barrel racer.

Practiced calf roping on the side.

My siblings, Daddy and Momma as my picnic table audience.

When the Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo (BPIR) trotted into Atlanta, Georgia, my farm family – grandpa, aunts, uncles, and cousins – piled in our motorcade of dually trucks.

Headed straight into the city.

For throwback Candace, BPIR measured up to a Toys “R” Us or Six Flags Over Georgia field trip.

Cowgirl Candace at BPIR 2022 held at Cowtown Coliseum in Fort Worth, Texas. | Photo By Kevin Dantes

Now back to me acting like I was strapped into some wild rollercoaster ride.

Aug. 5, 2023, the Georgia International Horse Park mentally teleported me to former cowgirl and rodeo life.

Carefree. At times a bit “Dennis the Menace” mannish in the stands.

My Momma pointed at me to “sit down before you fall.”

BPIR always reconnected me to the Southern music hits, concession stand food, and familiar faces decades prior.

I replay the family reunion fun with each new season.

My next favorite event starts: bareback bronc riding.

I’m wired with excitement.

The joust herks and jerks cowboy and bronc as a pair.

Aimed to unseat daring riders before the 8 seconds are up.

What the cowboy can’t do within these ticks:

Use his free hand for support.

Touch the horse with his legs.

Allow his heels to sink below the horse’s shoulder blades.

If the skilled cowhand can withstand curt up, down, left, right movements within that time frame, that’s a lucky start.

To hit the judging jackpot, the horse must give a bucking show.

The cowboy must resist with poise.

BPIR bareback-bronc rider and my mentor Billy Ray Thunder, 69, tested his decades-long technique for another year at the horse park.

Traditional twirls to the Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo’s ending theme song. | Photo By Kevin Dantes

During the Atlanta show of the 39-year Black touring rodeo, his golden hour attempt: lionhearted. But no win.

“You can’t second guess yourself once you commit,” said Thunder, who has braved bucking opponents for 32 years. “I gave it my best shot.”

The veteran rider and dear friend accepted the erratic duel for his last BPIR season.

Packing up his arena memories – training equipment and gear like his Justin Boots – for good when the competition concluded Sept. 22 in Washington, D.C.

“These are the only boots I practiced in,” he said. “They helped me get the job done.”

I hugged Thunder tightly for his legendary last ride and assured him that newer forms of riding are now ahead.

He simply smiled and headed toward the bucking chute.

BPIR support Tony Monts, 60, typically uses pre-show tailgating time to pep talk the night’s “cowboy protectors.”

Slumped in his lawn chair.

Armored in hometown Compton wear and Justin lace-up work boots.

“I’m all about comfort before it’s showtime,” Mont said.

I joined him for a second to eavesdrop on his pearls of wisdom to the younger cowboys.

Reminded me of the conversations Daddy gave me before I confronted life outside of our farm home.

On the opposite side of the arena, 84-year-old cowboy Adam Ezell Jr. walking caned a path to the concession area.

In elderly coolness.

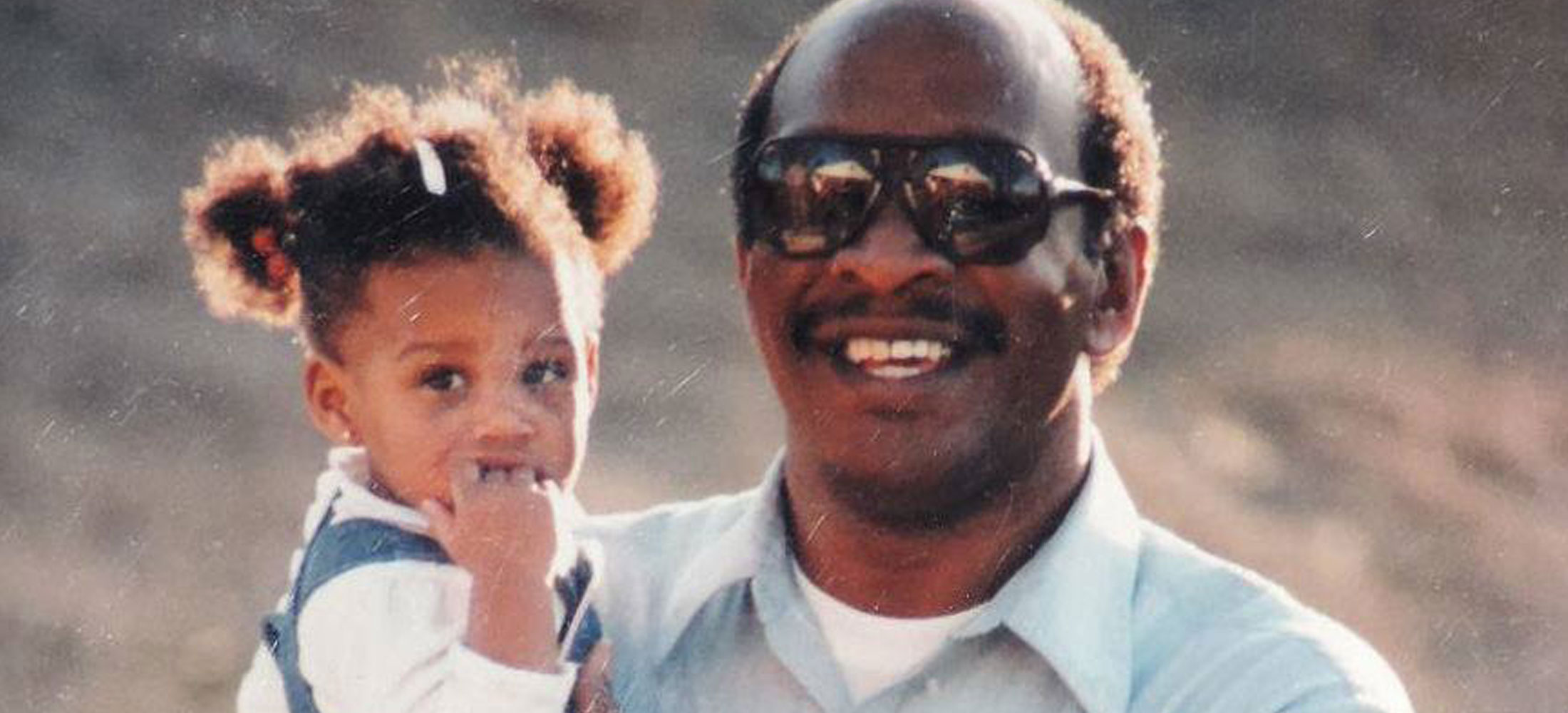

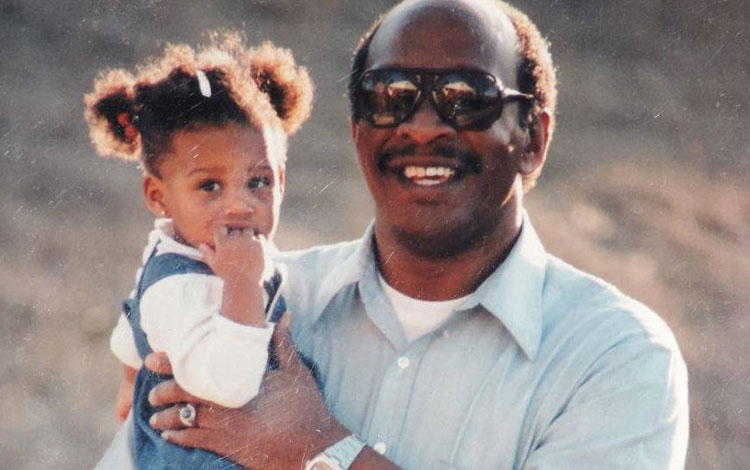

Toddler Cowgirl Candace in the 1980s with her late Grandpa Amos Morrow on Edward Hill Farm.

Just as my late Grandpa Amos Morrow would have high-stepped in his country's Western fashion.

A former BPIR relay racing champ, Ezell showboated an off-white, garnished yoked shirt. Sombrero. Bandana bolo tie. Plate belt buckle. Denim jeans. Brown boots.

I insisted on taking a photo album picture with him.

A mini photo shoot session automatically ensued.

“I grew up in the saddle,” said Ezell, who started Western riding at age 3 in Alabama, lived out west once upon a time, and now resides in Atlanta.

Ezell joined BPIR as a competitor during the all-Black rodeo’s 1984 inception.

On Aug. 5, he witnessed the sold-out show through the eyes of the same crunk crowds who rooted for him.

Bleacher seating reached its full capacity of 2,500.

The wise and proficient rider just smirked and waved to throwback spectators who remembered and recognized his BPIR contributions.

Ezell became a comrade to the late Lu Vason, BPIR founder.

Helping the rodeo pick up nationwide fans through original horsemanship and entertainment, Ezell and past arena athletes steadily drove audience numbers up.

Cowgirl Candace interviewing former BPIR contestant Adam Ezell Jr., 84, at the 2023 rodeo held in Atlanta, Georgia. | Photo By Kevin Dantes

To date, BPIR pulls in more than 130,000 spectators across major U.S. cities.

The rodeo’s moniker celebrates distinguished Black cowboy Bill Pickett, who originated the event known as bulldogging or steer wrestling.

Objective: Literally wrestle a steer to the ground with haste.

Descending a flying-pace horse.

Locking onto the steer’s horns.

Twisting its neck for the takedown.

Next to this sport and bareback, modern BPIR events now feature timed demonstrations of horsemanship.

The ladies compete in breakaway, steer undecorating, and barrel racing.

The fellas add in calf roping and bull riding (one of the most anticipated spectacles).

Both men and women form teams to relay race.

Youth participate in both junior breakaway roping and barrel racing.

All flashbacks to my home rodeo training days and the family road trips to watch the showmanship of my age group in action.

BPIR’s 2023 athletes included teens down to a 2-year-old competitor.

This season “The Greatest Show on Dirt” sold out in select cities: April’s Memphis, Tennessee, show; July’s Los Angeles, California, show; August’s Atlanta, Georgia, show; and September’s national championship show held in Washington, D.C.

And these arena moments repeatedly draw cowhands and onlookers who revel in the sport

Fitted in their flashiest rodeo attire.

The audience participation is electrifying.

The behind-the-scenes bonds are everlasting.

I scanned the arena and my face bellowed with joy.

I always imagine my siblings, Daddy, Momma, cousins, and family elders in that modern crowd.

The very reason why I continue to support newer generations who come into this sport.

Why my sideline cheer game is so melodramatic.

Why fellow participants believe I’m every youth riders’ parent.

A rodeo title I value and will hold proudly with every BPIR rodeo season.

Middle school Candace practicing her calf roping skills for her farm family’s feedback during the 1990s.

About Justin’s contributing writer: Candace Dantes

About Justin’s contributing writer: Candace Dantes is a fourth-generation farm girl and award-winning journalist based in the Georgia Black Belt Region. Currently, the print-to-digital content creator serves as communications director for national not-for-profit Outdoor Afro. She previously served as project manager and education journalist for U.S. Department of Agriculture research grant Black Farmers’ Network, and a content creator for Wrangler.

Photo by Tiffanie Page